Last July, the heads of state or government of the 27 EU member states, meeting as the European Council, agreed to a plan, developed at their request by the European Commission and labelled Next Generation EU, to borrow up to €750 billion on the capital markets to assist the member states in recovering from the economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Altering the Commission’s proposed distribution of €500 billion in grants and €250 billion in loans, the leaders agreed to distribute €390 billion as grants and €360 billion as loans to the member states to support investments and reforms essential for a sustainable recovery. The leaders also altered the Commission’s proposed uses of the funds, substantially increasing the funds that would be available through a new Recovery and Resilience Facility to support those investments and reforms. The new RRF will consist of €672.5 billion—€312.5 billion in 2018 prices in grants and €360 billion in loans. The €312.5 billion in 2018 prices is equivalent to €338 billion in current prices. In addition to the €672.5 billion for the RRF, the leaders approved €77.5 in grants for a variety of other uses. In addition to a grant, a member state can request a loan worth up to 6.8 percent of its 2019 Gross National Income. The funds will be distributed in 2021-24 through the EU’s seven-year Multiannual Fiscal Framework for 2021-27 and will be repaid over 30 years beginning in 2028.

After a prolonged disagreement last fall between Poland and Hungary, on one hand, and most of the other member states, and also between the German presidency of the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament, over a proposed regulation that would, under certain circumstances, provide for the suspension of disbursements under the recovery plan to a member state that violates the rule of law, the issue was eventually resolved—some would say finessed—in December when the European Council approved the Commission’s intention to adopt a Declaration to be entered into the minutes of the Council of Ministers when the latter decided on the rule-of-law regulation. The Declaration would state that the objective of the regulation is to protect the EU budget, its sound financial management, and the EU’s financial interests from any kind of fraud, corruption and conflict of interest, and that the application of the rule-of-law conditionality mechanism under the regulation will be “objective, fair, impartial and fact-based, ensuring due process, non-discrimination and equal treatment of Member States.” With that issue side-stepped, in late December the Parliament and Council—the latter unanimously, as required—approved the MFF, the EU’s seven-year budget; the NGEU, including the RRF; and the Own Resources Decision that would enable the EU to fund the MFF and service the €750 billion in debt that will be taken on to fund the RRF. On February 12, Regulation 2021/241 of the Parliament and Council establishing the RRF took effect.

The RRF regulation stipulates that reforms and investments under the Facility should help make the EU “more resilient and less dependent by diversifying key supply chains and thereby strengthening the strategic autonomy of the Union alongside an open economy….Recovery should be achieved, and the resilience of the Union and its Member States enhanced, through the support for measures that refer to the policy areas of European relevance structured in six pillars, namely: green transition; digital transformation; smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, including economic cohesion, jobs, productivity, competitiveness, research, development and innovation, and a well-functioning internal market with strong small and medium enterprises; social and territorial cohesion; health, and economic, social and institutional resilience with the aim of, inter alia, increasing crisis preparedness and crisis response capacity; and policies for the next generation, children and the youth, such as education and skills.”

The regulation requires the member states wishing to receive funds under the RRF to submit to the Commission a recovery and resilience plan that sets out the reform and investment agenda of the state and presents “measures for the implementation of reforms and public investment through a comprehensive and coherent package, which may also include public schemes that aim to incentivize private investment.” The plan was to be officially submitted, as a rule, by 30 April. The Commission is directed to “assess the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency and coherence” of the plan. In the event it gives the plan a positive assessment, it will submit a proposal to the Council to approve an implementing decision with the reforms and investment projects to be implemented by the state specified in the proposal. The Commission is expected to assess the submitted plans by the end of June and then translate each approved plan into a legally-binding act in a proposal to the Council, which will then have, as a rule, four weeks to adopt the proposal. The use of the term “as a rule” in the regulation makes it clear the deadlines for both the submission of a plan and the decision of the Council are elastic.

Adoption of the Commission proposal would pave the way for an initial disbursement of pre-financing to the member state in question—provided, of course, the Own Resources Decision (ORD) approved by the Council in December is approved by all of the member states. The ORD permanently increases the maximum level of resources that can be called from the member states from 1.2 percent of EU Gross National Income and provides for a temporary increase in the ceiling by an additional 0.6 percent of EU GNI for servicing the debt taken on to create the recovery fund. Thus far, no state has rejected the ORD. But there is nevertheless a huge question mark hanging over the ORD and, as a result, over the RRF; while the German Constitutional Court rejected last month an application for a preliminary injunction preventing Germany’s ratification of the ORD, it nevertheless said, in rejecting the application, that the constitutional complaint “is not clearly unfounded” and that it will conduct a thorough examination of the issues raised by the applicants. Without unanimous approval of the ORD by all 27 member states, the EU will not be able to go to the capital markets to raise and subsequently service €750 billion of debt and hence won’t be able to fund the RRF.

Notwithstanding the uncertainty in regard to the ORD and the RRF created by the German court’s decision, the EU member states moved forward with the process of submitting their recovery and resilience plans. As of Saturday, 13 of the 27 EU member states have submitted plans. Portugal, which currently holds the six-month rotating presidency of the Council, was the first member state to submit its plan, on April 22. Since then, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Spain France, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Austria, Slovakia and Slovenia have submitted plans. The Commission has made it clear that, while the Regulation creating the RRF states that plans are to be submitted “as a rule” by April 30, it will accept later submissions.

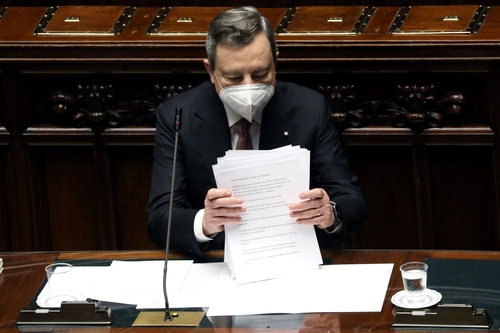

Not surprisingly, given the extent of detail requested in the 30-page Regulation, most of the plans that have been submitted are exceptionally long; the Belgian plan, for example, is 717 pages and the French plan 815 pages. The Spanish plan is, relative to the others, parsimonious, coming in at 348 pages. Also not surprisingly, all 13 have requested a grant but only a few have requested a loan. Most of the 13 have requested the maximum grant allowed under the criteria established in the RRF. Thus, Belgium has requested €5.9 billion, Denmark €1.6 billion, Germany €25.6 billion, Greece €17.8 billion, Spain €69.5 billion, France €40.9 billion, Italy €68.9 billion, Latvia €1.8 billion, Luxembourg €930 million, Austria €3.5 billion, Portugal €13.9 billion, Slovenia €1.8 billion, and Slovakia €6.3 billion. Only four requested a loan: Italy, the government of which is headed by someone who knows a lot about the subject, requested a loan of €122.6 billion. Greece requested a loan of €12.7 billion, Portugal a loan of €2.7 billion, and Slovenia a loan of €2.7 billion. Adding the grant and loan requests together, Italy has asked for the most support by far from the RRF—€191.5 billion—followed at some distance by Spain and France.

As if to underscore the EU member states’ need for assistance in recovering from the economic consequences of the continuing Covid pandemic, last Friday, as a number of recovery and resilience plans arrived in Brussels, the EU’s preliminary flash estimate of GDP for the first quarter of 2021 issued that day indicated the EU is again in a recession, as conventionally-defined by two consecutive quarters of negative growth. After contracting by 11 percent in the second quarter last year in the wake of the first wave of the pandemic and then increasing by 12 percent in the third quarter as the lockdowns and other restrictions were relaxed, the seasonally-adjusted GDP of the EU dropped by 0.5 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020 and by 0.4 percent in the first quarter of 2021. But interestingly, although the EU as a whole experienced modest contractions in fourth and first quarters and the members of the euro area experienced slightly larger contractions of 0.7 and 0.6 in those quarters, only one state, Italy, with contractions of 1.8 percent in the fourth quarter and 0.4 percent in the first quarter, is currently in a recession. Nevertheless, some of the member states experienced significant contractions in one of the two quarters—most notably, France, with a contraction of 1.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020, and Germany, with a contraction of 1.7 percent in the first quarter of 2021. And Spain just missed qualifying as being in a recession, with a growth rate of 0 in the fourth quarter and -0.5 in the first quarter.

The investments and reforms that will be undertaken by the member states that make use of the EU’s new Recovery and Resilience Facility are no doubt essential for a sustainable recovery from the economic consequences of the Covid pandemic and a future resilience from any such crisis. But while the member states’ recovery and resilience plans are being evaluated by the Commission and Council and then, assuming all goes well with the approval of the ORD, the funds are raised and the member states begin the task of implementing the investments and reforms, the EU needs to do more right now to boost growth and ensure that the member states, and the EU as a whole, avoid a “third-wave” recession. What the EU needs more than anything else right now is a good old-fashioned fiscal stimulus.

David R. Cameron is a professor of political science and director of the European Union Studies Program at the MacMillan Center.